Celebrating Braille

4th January is World Braille Day! If you are a braille reader yourself, or have a personal or professional interest in accessibility for people who are blind, here is an insight into some interesting things about braille that you may not already know.

Braille comes in two forms – Uncontracted and Contracted Braille

Uncontracted braille

(also known as Grade 1 braille) is a letter-by-letter translation from print, where every letter is individually represented in braille. This is usually the first step for people learning to read braille.

Contracted braille

Also known as Grade 2 braille, it's usually used by more experienced braille users. It essentially shortens many common words, and acts as a kind of shorthand and also uses a number of extra signs. It benefits people who use braille as it’s quicker to read and takes up less space.

You can learn braille at any age

The majority of people who lose their sight do so later in life, and there’s a common misconception that learning braille as an adult is difficult. However many people who learn braille later in life do so successfully.

There are lots of courses and information available – check out the RNIB website for information on braille courses for children and adults. Even a little braille can make a big difference to independence and enjoyment after sight loss.

Braille isn’t a language of its own

Braille is a tactile reading and writing code that can be used to write and read many languages. It enables people who are blind or partially sighted to read and write by touch using their fingertips.

So rather than a language in itself - as you might consider BSL for example – braille is a translation where a combination of raised dots represent letters, numbers, words and punctuation.

In some languages there are specialist combinations, such as letters with accents. With uncontracted braille, each character is represented letter-by-letter and so it is read in the language its translated from.

There are braille versions of English, Chinese, Arabic, Hebrew and many other languages.

There used to be several different braille codes in English-speaking countries – now there’s one in common use.

In the early 90s, the International Council on English Braille ()ICEB) had concerns that the ‘complexity and disarray’ of the many braille codes was a ‘significant factor in the erosion of braille usage’. So it collaborated with the major English-speaking countries to develop and produce a unified braille code across English-speaking parts of the world. Prior to this there were several different versions used around the world, including English Braille American Edition (EBAE) in North America and Standard English Braille (SEB) was used in the UK.

United English Braille (UEB) is now the official braille code used by English-speaking countries around the world - including the UK, North America, Australia, Canada, South Africa, Ireland, Nigeria and Singapore.

You can read more about the process and recommendations for the development of UEB in A Uniform Braille Code by TV Cranmer and A Nemeth, 1991 on the ICEB website. This also has the most up to date braille ‘rules’.

Braille books are massive!

Braille takes up a lot of space on a page compared to traditional print. For this reason, carrying around or reading a braille book might be more cumbersome than their printed equivalents. For example, the braille version of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix weighs around 26lb and the Websters Unabridged Dictionary consists of 72 volumes.

For this reason, it’s easier to read braille on the go using a portable electronic braille display or to read audio books through apps such as EasyReader.

Braille isn’t always read on paper

These days, there is a choice of how to read braille: printed (embossed) or with electronic braille displays.

When it’s not practical for braille users to read information on print outs – when reading websites or electronic documents for example - many braille users use an electronic braille display.

Braille displays are used with screen readers. These gather the content of a computer screen and convert it into braille characters which are then read on the display.

Braille displays typically have a single line of braille cells – with round-tipped pins that raise up and down under a flat surface – these change to represent and display all the different braille characters on the line being read.

These can be carried around and plugged in to computers and are used to explore websites, read emails and electronic documents. Use EasyConverter Express to produce braille documents to print out or read on an electronic braille display.

Printed braille can be impractical as it’s heavy to carry lots of paper. It can take up a lot of space, and braille books can be expensive and time-consuming to produce. This being said, new accessibility software like Dolphin EasyConverter Express makes printing and producing accessible documents much quicker and easier. So if you’re printing documents or letters for a diverse group of people, this type of software is a must-have.

Braille Terminology

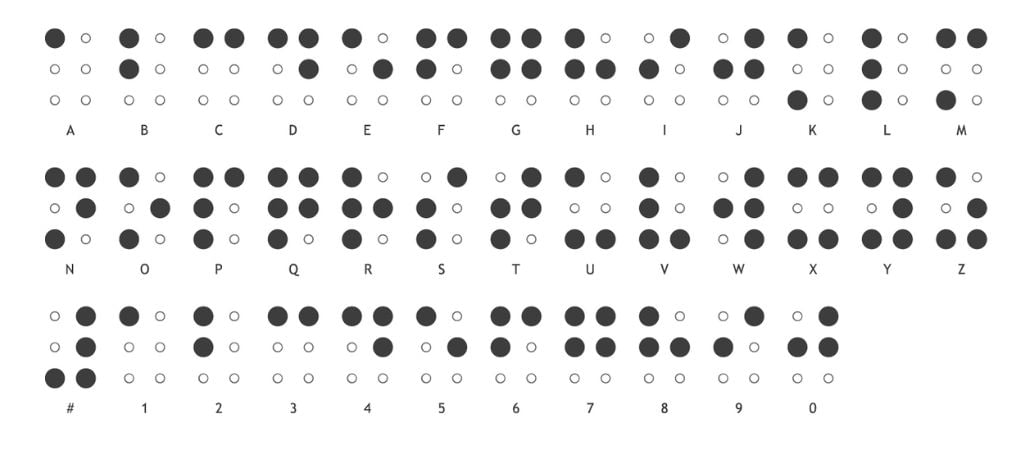

- Each character is represented by a cell.

- A cell consists of six tactile dots

- Dots are configured in different ways, to represent the letters of the alphabet, numbers and punctuation.

- The combination of dots in each cell are raised on the page, or on the braille display, so they can be felt by the reader

- Braille is read by moving the fingertips from left to right along the line

- Usually both hands are used, one to read the letters and the other to move to the next line and identify the readers’ place on the page

- Braille might be read using an electric Braille Display, or on paper which has been put through a braille embosser or braille printer (not to be confused with an ‘ink printer’) to raise the tactile dots.

Not every person who is blind reads braille

The RNIB state that around 7% of people who are registered blind or partially sighted use braille in the UK.

The RNIB recommends that people who are losing their sight or are partially sighted learn braille by touch rather than by sight. This means that if sight deteriorates further, braille touch readers will have a head start, even though it can take a while to get used to. There are resources and courses to learn braille for children, adults, for touch learners and sight learners.

According to the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) In the USA, fewer than 10% of 1.3 million legally blind people use braille to read - and only ten percent of children with visual impairments in the USA are learning braille.

Compare this to the 1950s, when more than half the US population of children who are blind were learning to read braille. The increase in the amount of technology available now for people who are blind is an obvious contributory factor, and while the world is certainly more accessible, there is some debate as to the consequences of a reduction in braille use on the literacy of children who are blind.

There are braille codes for music, science and maths

The Nemeth Braille code for Mathematics is a braille code for maths and science using standard six-dot braille cells for tactile reading. These include braille codes for geometry, fractions, triangles, and arrows, as well as numbers and signs. Nemeth Code was integrated into UEB in 1992.

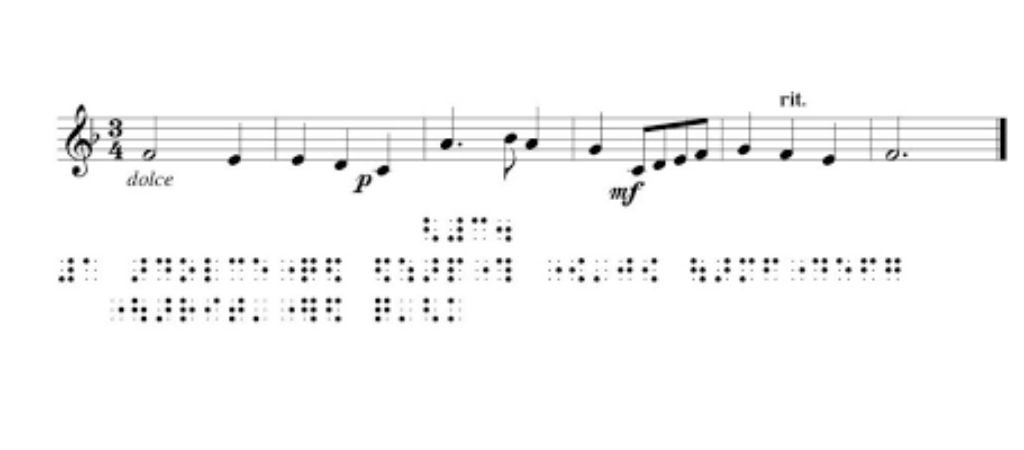

Braille Music is a braille code that allows music to be notated using braille cells, so music can be read by musicians with visual impairments.

Another of Louis Braille’s inventions, Braille music uses the same six-dot cells, but in braille music, it has its own meanings, combinations, abbreviations and principles.

There are Braille versions of popular family games

Toy manufacturers around the world have used braille to help children with visual impairments connect with others and learn through play.

LEGO Braille Bricks were introduced in 2020 and distributed around the world, free of charge, to selected schools and services that educate blind and visually impaired children. LEGO Braille Bricks are a way for children to learn braille by playing with specially designed blocks.

Introducing braille through fun activities and games, each block in the LEGO Braille Bricks collection has a printed character along with the braille code for that letter, number or symbol evident in the raised rivets on the brick’s surface.

Toy manufacturer Mattel have released accessible versions of bestselling games such as Uno and Scrabble available to mainstream and specialist suppliers around the world. This ensures that these popular card and board games can be enjoyed by the whole family.

For traditionalists, you only need to be able to read 15 braille letters to play card games like snap with a braille version of playing cards.

Other Dolphin Blogs that might interest you

In this blog, Aj Ahmed describes the positive impact reading braille had on his education, work and family life. Along with his thoughts on the continued importance of braille for young people who are blind.

Our partners at Calibre Audio explore some of the many benefits of reading on development, education and wellbeing.

4 ways SuperNova Makes Reading Accessible

Dolphin recognises everyone has a right to be able to read in a way that suits their vision. It’s our mission to build software that empowers people with visual impairments to read and succeed.

Let Us Know What You Thought about this Post.

Write your comment below.